The Beddington Medal is the BSDB’s major commendation to promising young biologists, awarded for the best PhD thesis in Developmental Biology defended in the year previous to the award. Rosa Beddington was one of the greatest talents and inspirational leaders in the field of developmental biology. Rosa made an enormous contribution to the field in general and to the BSDB in particular, so it seemed entirely appropriate that the Society should establish a lasting memorial to her. The design of the medal, mice on a stylised DNA helix, is from artwork by Rosa herself.

Like many years, it was a tough decision for the BSBD committee to choose a winner for the 2024 Beddington medal. We are pleased to announce that this goes to Delan Alasaadi, for his PhD work at UCL on the role of tissue mechanics in neural crest induction.

I have written many letters on behalf of numerous students to support their applications for various prizes, jobs, and positions, including several previous Beddington Medal applications. However, writing a letter supporting Delan Alasaadi for this award comes with great ease, as Delan has been an excellent Ph.D. student.

I have written many letters on behalf of numerous students to support their applications for various prizes, jobs, and positions, including several previous Beddington Medal applications. However, writing a letter supporting Delan Alasaadi for this award comes with great ease, as Delan has been an excellent Ph.D. student.

Delan developed great curiosity; he continuously engaged with his colleagues in discussions during our lab meetings and beyond. With unique ambition, he sought novel ideas to test in his project. With impeccable determination, breaking the physical barrier, he established collaborations and sought expertise across Europe and other continents, learning the most challenging techniques and valuable lessons.

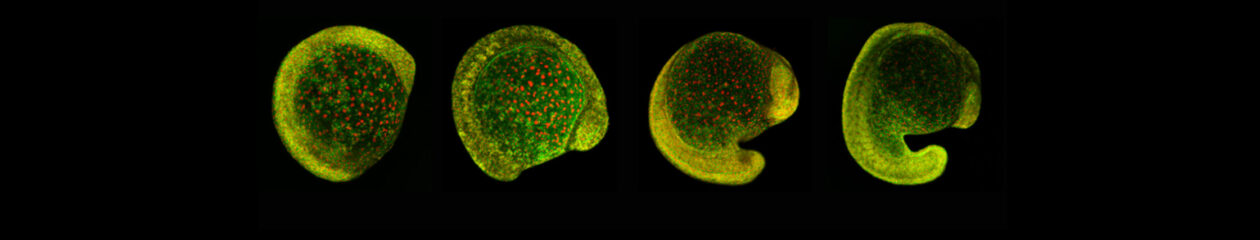

Delan’s PhD thesis was about the role that tissue mechanics could play in neural crest induction. This was a risky project because of the lack of tools to measure and modify mechanics in vivo. Delan spent the first part of his Ph.D. designing biophysical tools to investigate the feasibility of the question at hand, showing great creativity in his experimental approaches. Embryonic induction is the process by which a group of cells sends signals to adjacent tissues, changing their differentiation fate. An important aspect of embryonic induction, which has been poorly studied, is how the receiving tissue regulates the response to the inductive signals—a process known as ‘competence.’ Additionally, while the molecules involved in embryonic induction have been identified, the role of mechanical cues in this process has remained largely unexplored. Delan found that during early development, the hydrostatic pressure of the blastocoel cavity increases. This increase is sensed by the ectoderm cells above the cavity, modulating Yap activity, which in turn regulates the response to Wnt signaling—a key player during neural crest induction. Thus, Delan found, for the first time, the mechanism that could explain the loss of neural crest competence during development: the increased hydrostatic pressure leads to the retention of Yap/b-catenin in the cytoplasm, impairing neural crest induction even in the presence of the inducer Wnt (loss of competence). Delan showed that this mechanism is conserved in embryos of different species (e.g., amphibians, mice, humans). This work has been recently accepted in Nature Cell Biology (2024), with Delan as the sole first author.

There are two important aspects of how Delan approaches research that make him a deserving winner of the Beddington Medal:

Fearless and ambitious: There was not a single technique or experiment that Delan did not learn if he considered it necessary to address his PhD project. Consequently, he set up in my lab many techniques that we did not have, such as micropipette aspiration, microcomputed tomography, Micro-pressure probe (servo-null) to measure hydrostatic pressure, and in vivo biophysical tools among others.

Commitment: Not only did he work countless hours and overcome the limitations of developing his PhD during the COVID-19 pandemic, but he also showed a commitment to his work and experiments that is difficult to find. Just one example: he wanted to measure the hydrostatic pressure inside the embryo, but there are only a few labs worldwide that have the equipment and expertise to do it. He found a lab in the Netherlands that could teach him the technique, but we failed to get a source of Xenopus embryos from the Netherlands; instead, we got embryos from Belgium. So, every day, Delan had to travel to Belgium in the morning, get recently fertilized embryos that he kept in a low-temperature incubator on the train, and rush back to the lab in the Netherlands to conduct the experiments. He succeeded!

In addition to his main Ph.D. work accepted in Nature Cell Biology, he is the co-first author of another paper published in Developmental Biology about neural crest migration and the first author in a two-author review to be published in the journal Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences titled “Mechanically guided cell fate determination in early development,” written entirely by Delan.

In conclusion, Delan has been the only and mighty driving force behind his PhD work, identifying for the first time that mechanics (hydrostatic pressure) controls embryonic competence. His findings resolve a 100-year-old question: how embryonic competence is regulated, and which implications in stem cell research and cell therapy approaches? He is a motivated and dedicated young researcher, and all his efforts deserve to be recognized with an award such as the Beddington Medal. Therefore, I support this application in the strongest way possible.

- Roberto Mayor

Published work:

Alasaadi DN, Mayor R. Mechanically guided cell fate determination in early development. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024 May 30;81(1):242. doi: 10.1007/s00018-024-05272-6. PMID: 38811420; PMCID: PMC11136904.

Alasaadi DN, et.al. Competence for neural crest induction is controlled by hydrostatic pressure through Yap. Nat Cell Biol. 2024 Apr;26(4):530-541. doi: 10.1038/s41556-024-01378-y. Epub 2024 Mar 18. PMID: 38499770; PMCID: PMC11021196.

Barriga EH, Alasaadi DN, et. al. RanBP1 plays an essential role in directed migration of neural crest cells during development. Dev Biol. 2022 Dec;492:79-86. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2022.09.010. Epub 2022 Oct 4. PMID: 36206829.

It is with great pleasure that we nominate Professor Petra Hajkova for the Cheryll Tickle Medal. Petra has become such an established member of the field that it will surprise many to learn that she started her lab just 14 years ago. In this short time she has risen through the ranks at the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences (LMS) from junior group leader (2009) to Epigenetic Section Chair (2018) and on to the Interim Director (2021-2022). All the while she has continued to make the major scientific contributions that have been her hallmark since the start of her research career.

It is with great pleasure that we nominate Professor Petra Hajkova for the Cheryll Tickle Medal. Petra has become such an established member of the field that it will surprise many to learn that she started her lab just 14 years ago. In this short time she has risen through the ranks at the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences (LMS) from junior group leader (2009) to Epigenetic Section Chair (2018) and on to the Interim Director (2021-2022). All the while she has continued to make the major scientific contributions that have been her hallmark since the start of her research career.

We are very happy to announce that this year’s winner of the BSDB Wolpert medal is Prof. Sally Lowell from the University of Edinburgh.

We are very happy to announce that this year’s winner of the BSDB Wolpert medal is Prof. Sally Lowell from the University of Edinburgh. Until a few months ago, Sally was our BSDB meeting secretary and she was outstanding in this role, bringing many new initiatives including the BSDB childcare and disability travel awards. She pushed hard in many ways for diversity, inclusivity and sustainability, so that during her tenure the BSDB became one of the leading drivers of new ways of running conferences. This climaxed with our recent hosting of the European Dev Biol Congress where she pushed for – and made work – a programme made up largely of ECR speakers from across Europe, with a unique three hub arrangement with interdigitating talks beamed in from Paris and Barcelona to the central host hub of Oxford. This was a pioneering “experiment” that could have gone badly wrong, but instead worked exceptionally well, and will have set a precedent for others to follow. Several colleagues from sister dev biol societies across Europe congratulated us on how brave the BSDB was to run such a meeting and how successful it had been. This kudos for the BSDB was largely down to Sally.

Until a few months ago, Sally was our BSDB meeting secretary and she was outstanding in this role, bringing many new initiatives including the BSDB childcare and disability travel awards. She pushed hard in many ways for diversity, inclusivity and sustainability, so that during her tenure the BSDB became one of the leading drivers of new ways of running conferences. This climaxed with our recent hosting of the European Dev Biol Congress where she pushed for – and made work – a programme made up largely of ECR speakers from across Europe, with a unique three hub arrangement with interdigitating talks beamed in from Paris and Barcelona to the central host hub of Oxford. This was a pioneering “experiment” that could have gone badly wrong, but instead worked exceptionally well, and will have set a precedent for others to follow. Several colleagues from sister dev biol societies across Europe congratulated us on how brave the BSDB was to run such a meeting and how successful it had been. This kudos for the BSDB was largely down to Sally. The

The  Originally trained as an engineer and physicist, JP Vincent became a developmental biologist by accident, when his PhD advisor George Oster, a mechanical engineer turned biologist, suggested that he look at the fluid dynamics of Xenopus eggs. He was lucky to be hosted by John Gerhart for the wet part of this project and was quickly taken by the warmth of the developmental biology community and the range of questions that developmental biology addresses. Since then, JP has been inspired by classical questions of developmental biology such as axis formation, cell fate determination, morphogen gradient formation and tissue renewal, and strived to bring methods from other disciplines to address them. His work has questioned established dogma, uncovered new mechanisms, and brought outsiders into the developmental biology field.

Originally trained as an engineer and physicist, JP Vincent became a developmental biologist by accident, when his PhD advisor George Oster, a mechanical engineer turned biologist, suggested that he look at the fluid dynamics of Xenopus eggs. He was lucky to be hosted by John Gerhart for the wet part of this project and was quickly taken by the warmth of the developmental biology community and the range of questions that developmental biology addresses. Since then, JP has been inspired by classical questions of developmental biology such as axis formation, cell fate determination, morphogen gradient formation and tissue renewal, and strived to bring methods from other disciplines to address them. His work has questioned established dogma, uncovered new mechanisms, and brought outsiders into the developmental biology field.