Following a generous donation, the BSDB has instituted the Dennis Summerbell Lecture, to be delivered at its annual Autumn Meeting by a junior researcher at either PhD or Post-doctoral level. The 2017 lecture awardee was Helen Weavers (School of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, University of Bristol) with her submitted abstract “Understanding the inflammatory response to tissue damage in Drosophila: a complex interplay of pro-inflammatory attractant signals, developmental priming and tissue cyto-protection”. Her award lecture was presented at the Autumn Meeting 2017, jointly organised by the BSDB together with the Swedish, Finish, Norwegian and Danish Societies of Developmental Biology, 25-27 October 2017 in Stockholm.

Following a generous donation, the BSDB has instituted the Dennis Summerbell Lecture, to be delivered at its annual Autumn Meeting by a junior researcher at either PhD or Post-doctoral level. The 2017 lecture awardee was Helen Weavers (School of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, University of Bristol) with her submitted abstract “Understanding the inflammatory response to tissue damage in Drosophila: a complex interplay of pro-inflammatory attractant signals, developmental priming and tissue cyto-protection”. Her award lecture was presented at the Autumn Meeting 2017, jointly organised by the BSDB together with the Swedish, Finish, Norwegian and Danish Societies of Developmental Biology, 25-27 October 2017 in Stockholm.Helen’s work so far

After completing her PhD studies investigating Drosophila nephrogenesis in Helen Skaer’s lab in Cambridge, Helen moved to Bristol in 2013 to take up a 5 year, MRC-funded post-doc position between Paul Martin’s and Will Wood’s labs. Her first publication from this work (Weavers et al., 2016, Cell 165, 1658ff.), showed that Drosophila macrophages (haemocytes), must first be “primed” by engulfing at least one dead cell, before they are responsive to wound attractants. These findings are important because the majority of human pathologies are a consequence of too little or too much inflammation. What really excited the judges of the Denis Summberbell Lecture award was the work which had led to her most recent paper entitled “Systems Analysis of the Dynamic Inflammatory Response to Tissue Damage Reveals Spatiotemporal Properties of the Wound Attractant Gradient” (Weavers et al., 2016, Curr Biol 26, 1974ff.). This was a true multidisciplinary study, using a combined approach of mathematics and biology to analyse macrophage behaviours in response to tissue damage. Although the identity of the wound attractant signal/s are still not clear, this study was able to determine several of the characteristics of the attractant(s). Building on this strong platform of work, Helen is currently developing her own research towards understanding tissue protection/resilience in Drosophila and man, and this was an exciting novel element of her award lecture. In her talk, she described in a stunningly visual and understandable way how successful tissue repair relies not only on the host’s ability to mount an effective inflammatory response, but also on its ability to limit it. Her talk was a fabulous highlight and a shining example of high quality research by members of the BSDB.

Lecture abstract:

Understanding the inflammatory response to tissue damage in Drosophila: a complex interplay of pro-inflammatory attractant signals, developmental priming and tissue cyto-protection

Understanding the inflammatory response to tissue damage in Drosophila: a complex interplay of pro-inflammatory attractant signals, developmental priming and tissue cyto-protection

Helen Weavers, Bristol, UK

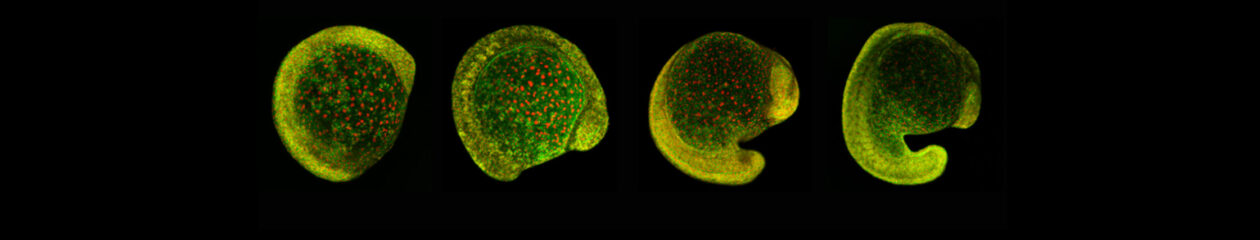

An effective inflammatory response is pivotal to fight infection, clear debris and orchestrate the repair of injured tissues; however, inflammation must be tightly regulated since many human disease pathologies are a consequence of inflammation gone awry. Using a genetically tractable Drosophila model, I use precise genetic manipulation, live imaging and computational modelling to dissect the mechanisms that activate the inflammatory response to tissue damage and those that simultaneously protect the regenerating tissue from immunopathology. Upon tissue damage, immune cells (particularly neutrophils and macrophages) are recruited into the damaged area by damage signals (danger-associated molecular patterns, DAMPs) released from the injured tissue. In collaboration with computational biologists, we employ a sophisticated Bayesian statistical approach to uncover novel details of the pro-inflammatory wound attractants, by analysing the spatio-temporal behaviour of Drosophila immune cells as they respond to wounds. We show that the wound attractant is released by wound edge cells and spreads slowly through the tissue, at rates far slower than small molecule DAMPs such as ATP and H2O2. Strikingly, we also find that immune cells must be developmentally ‘primed’ by uptake of apoptotic corpses before they can respond to these damage attractant signals. Such corpse-induced priming is an example of “innate immune memory” and may serve to amplify the inflammatory response in situations involving excessive cell death – and otherwise limit an overzealous and damaging immune response. Indeed, whilst inflammation is clearly beneficial, toxic molecules (e.g. reactive oxygen species, ROS) generated by immune cells to fight infection, can also cause significant bystander damage to host tissue and delay repair – and may underpin chronic wound-healing pathologies in the clinic. To counter this, I find that wounded Drosophila tissue employs a complex network of cyto-protective pathways that promote tissue ‘resilience’, which both protect against ROS-induced damage and stimulate damage repair. Successful tissue repair, therefore, not only relies on the host’s ability to mount an effective inflammatory response, but also its ability to finely tune it and limit associated immunopathology.